Ally Read online

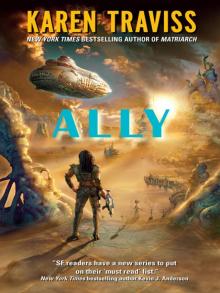

KAREN TRAVISS

ALLY

For Jim Gilmer, the man with the compass.

Contents

Prologue

One down, one to go.

1

The sheven reared from the marshes, and suddenly it was…

2

Esganikan Gai liked the bulkhead of her cabin set to…

3

Every world that Eddie Michallat knew was already full of…

4

“I don’t care,” said Lindsay.

5

Aras could smell the excitement rolling off the marines—including Ade.

6

Shan squinted against the spray flying from the bow of…

7

Umeh Station’s geodesic dome had taken more than a few…

8

“They never learn, do they?” said Shan.

9

The isenj troops manning the barricade in front of the…

10

“So how many dead?” asked Mick, the duty news editor,…

11

Wess’har, Ade had said, had no external testicles. But when…

12

There was nothing the isenj could do to Umeh Station…

13

They were eggs all right.

14

An almost-familiar bronze cigar of a ship, a castoff of…

15

Lindsay didn’t see the boat come ashore: none of them…

16

Shan sat cross-legged in the grass, eyes closed, enjoying something…

17

“Hi, Lin,” said Shan. “You’ve let yourself go a bit,…

18

“A month? Oh Christ, no.”

19

“I’m glad you decided to come,” said Esganikan.

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise

Other Books by Karen Traviss

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

The Temporary City, Bezer’ej, Cavanagh’s Star system: interrogation room

One down, one to go.

Shan Frankland had two ways of tracking Lindsay bloody Neville: to let the Eqbas find her by scanning the sea or by squeezing information out of Mohan Rayat and doing the job herself, like she always had.

Lindsay had to be found before she did something stupid.

I should have shot her when I had the chance and when she could still be killed. The second chance, fuck it. And Rayat, too. Christ, I’m getting slack.

Rayat watched Shan walk around the room without moving his head. She knew when someone was following her in their peripheral vision by the fixed stare ahead and the blink rate; but Rayat didn’t blink.

He was a spook. He was trained for this. Sod it, she’d make him blink. She was a copper, so she was trained for it too.

“So where do you think she’s gone?” Shan asked.

Rayat didn’t move a muscle. “No idea. It’s a big ocean, and Lindsay’s an unpredictable woman.”

“You wouldn’t be shitting me, of course.”

“Would I have turned myself in if I was colluding with her?”

Shan thought of a few scenarios where he might have done just that. She wouldn’t trust him as far as she could spit in a Force Ten. “You tell me.”

“I’ve seen what this parasite can do and it scares me.”

“So have I. “C’naatat had kept her alive through a shot-shattered skull and drowning and even drifting in the vacuum of space minus a suit. Scared? You have no idea, chum. She paused in front of him and folded her arms: he sat at the bare table with his hands folded. “You used to call it a symbiont. You’re a scientist. You’re precise about terminology.”

“Symbionts are about mutual benefit. Parasites are about keeping you as alive as you need to be for their benefit.”

“It wants to reproduce and find new hosts, that’s for sure.”

“So you can’t kill me easily. You know that.”

“I know. Consider it an incentive for me.”

Shan stared him in the eye until he looked away. She had no intention of giving in again to her urge to punch that smirk off his face. Whatever you threw at a c’naatat host, it made them stronger: the organism adapted instantly with a nifty work-round, cheating death with disturbing ease, and the host came out with a new healing adaptation. No, she wasn’t going to oblige Rayat by making a supersoldier out of him. It was bad enough that he’d been infected with a strain of c’naatat that now knew how to keep her alive in space.

The bastard had been sent to secure the organism for the European federal government. Like her, he didn’t abandon his mission just because things got awkward. She hated him with the passion you could only muster for someone who showed you the worst aspects of yourself.

“Well, you’re not going anywhere now,” said Shan. “And neither is Lin.”

“Vengeance is a powerful focus.”

“Not vengeance. Just stopping someone who takes decisions to change the course of the fucking universe at the drop of a hat. You know. Nuke an island, near as damn it wipe out the bezeri, change a whole ecology, that kind of stuff.” She was getting mad now: her fists went involuntarily to her hips and she felt her jaw set. “Her and her poxy humanitarian conscience—and don’t tell me she’s found religion. That’d just piss me off even more. It’s bad enough that she thinks she knows best every time, without her thinking she’s got a hotline to God for mission tasking.”

Rayat considered Shan with a benign hint of a smile. “Take the word God out of that stream of vitriol, and you might well be describing yourself.”

“Nice try,” said Shan quietly. “But I’m past having pissing contests with you.”

He carried on anyway. “Or your wess’har friends. You all make those epic decisions so easily.”

“I’ll stick another one on the list, then,” said Shan. For all his spook expertise at reading people’s reactions, Rayat didn’t know what was in her head right then, what was preoccupying her. He didn’t know the decisions she’d had to make. “Either way, c’naatat stays here and nobody else picks up a dose. EnHaz might be long gone, but I’m not, and I’m still on duty.”

Rayat looked at her with dark eyes that might have betrayed a hint of kindness had they not been his. She wondered how long her self-control would stop her thrashing him the way she had before he picked up c’naatat. She also wondered how many of her memories—and Ade’s, and Aras’s—were surfacing in this smug bastard’s mind. She hoped they’d be the worst ones, like stepping out of the airlock into the void, a slower way to die than most imagined.

But Rayat didn’t know all the decisions she’d had to take. She’d aborted her own child. Killing Rayat and Lindsay Neville wouldn’t trouble her at all, provided she had enough explosive power to do the job. She wondered again why she hadn’t done it already, when all it would have taken was one round in the head.

It struck her that it wasn’t Lindsay Neville she needed to find. It was the Shan Frankland that she used to be who was missing.

1

I fail to understand why gethes talk about individuals versus society. They are the same thing. The action of every individual counts, and those individual acts of personal responsibility accumulate to create society. Snowflakes are equally blind to their role in causing avalanches.

SIYYAS BUR, matriarch historian

on early encounters with human colonists on Bezer’ej

Seguor Marshes near the former colony of Constantine, Bezer’ej: 2377

The sheven reared from the marshes, and suddenly it was a plastic bag dragged dripping from a polluted river and falling back into the water with a splash.

Aras had never seen that river and he’d never seen

Earth. But the memory was vivid, and it wasn’t his.

“I hate those bloody things.” Ade Bennett peered over the edge of the skiff, rifle ready. “How big do they get?”

“Did you live near a river once?”

“What?”

“A river. A memory. It feels like yours. Plastic waste in a river.”

“Maybe.” Ade’s gaze stayed fixed on the marshes. “Might be Shan’s. We’ve both seen plenty of shit at home.” He turned his head slightly, eyes still darting back to the sheven’s last location, ever the vigilant soldier. “Come on, how big?”

Aras’s c’naatat parasite, efficiently filing recollections from other hosts, had absorbed the memory of the river either from Ade, or from Shan, their mutual isan—their “missus,” as Ade put it. The snapshot of the humans’ filthy homeworld was shared between them by an organism that adapted, preserved and repaired its host in the face of all threats except fragmentation.

“Three meters, perhaps.” Aras considered the range of sheven he had seen over the years. They lurked just beneath the surface, emerging only to snatch prey and plunge back beneath the surface. “I saw one that size a century ago, but most of them are two meters or smaller.”

“Bloody awful way to die, being digested by a bit of cling-wrap.”

“But you wouldn’t die. C’naatat wouldn’t allow it.”

“Bloody awful way to give the thing indigestion, then.” Ade had a quiet persistence when it came to pursuing ideas. “So what would happen? Would I sort of sit there in its guts until it threw up? I mean, do they have arses? Would it shit me out?”

“You might infect it, of course, in which case you might remain within it.” It was unhappy speculation, but nothing that Aras hadn’t considered himself in the five centuries since he’d become a host to the organism. “But c’naatat seems to favor more complex hosts than a sheven.”

“I feel so much better. Thanks.”

C’naatat certainly favored humans. They were hunting an infected human now; Commander Lindsay Neville was somewhere out there in the waters beyond this estuary, an altered woman living underwater with the native cephalopod bezeri. Aras now wondered if Ade had been right to infect her deliberately.

You were seconds away from doing it yourself.

“No bezeri,” said Ade.

“With so few left, I doubt we would spot them now.”

“It sounds like Lindsay at least got them organized.”

“You’re still asking if you made a mistake giving her c’naatat.”

“I’m still feeling like an arsehole, yes.”

“If you hadn’t, I would be down there now.”

Ade’s focus on the water seemed unnaturally intense.

“Shan would have gone ballistic either way. Maybe it doesn’t make any difference.”

It wasn’t Ade’s fault. It had almost been a joint decision. The bezeri needed help of the kind only a c’naatat could give, and if Ade hadn’t stopped him, Aras would have been where Lindsay was now, helping the bezeri salvage what they could of their shattered society.

“I think you made the right decision. I believe Lindsay Neville has found a sense of responsibility and will do as much as I ever could.”

“What if you’d known the bezeri had exterminated a whole bloody race? Would you have been so quick to put your arse on the line for them then?”

“Their ancestors committed genocide. Not this generation. Nor the generation I aided in the past.”

“You smelled bloody shocked when you found out.”

“I was.”

“Do you believe Rayat, though? He’s a lying bastard. Maybe it’s part of some ruse.”

“No,” said Aras. He wanted desperately to see the bezeri again. He wanted to confront them about it. “I believe him. It serves no purpose to tell me a lie about their past, and it explains a great deal.”

“I’m not sure I give a fuck about them any more.”

“Hindsight.”

“Reality. They’re no better than us. Maybe this serves the fuckers right. Poetic justice.”

Aras had always seen the bezeri as victims. They had been the victims of the isenj colonists, and them the victims of the gethes, the carrion-eating humans of the Thetis mission. They were collateral damage, to use Ade’s jargon.

“It doesn’t alter what Lindsay and Rayat did to them,” said Aras. He labored patiently through human moral logic. “Even if bezeri see no shame in genocide, their ancestors carried out the slaughter, not this generation. They didn’t earn their own destruction.”

“But they aren’t apologizing for it, either, are they?”

“Motive is irrelevant. Only outcomes count.”

“I’m still too human to believe that, mate. Motive matters.”

Intent was an oddly human factor. Aras knew that very well, but sometimes he slipped back into human thinking, and the wess’har and human perspectives on guilt and responsibility could never align. Of all the differences between the species, that was the one that Ade had never come to terms with. Not even Shan had, and she was a wess’har-minded human even before she absorbed the genes.

“No,” said Aras. “It doesn’t matter. The only thing that counts is what’s done.”

Ade lay against the gunwales of the boat with his rifle trained on the water, a grenade launcher bolted to its muzzle. Lindsay Neville had walked ashore around here once; she might do so again. Her baby son was buried here.

“We must’ve just missed her last time we were out this way,” he said. “I know Shan said she wanted her alive, but I’m still not sure she’ll slot the bitch and have done with it.”

“Then we take the opportunity if we get it.” The transparent sheven, no more than one single, insatiable digestive tract, broke the surface of the water twenty meters ahead of them, staying close to the shoreline, where its prey—small crawling creatures—was most likely to stray too close. This kind of sheven was a freshwater predator of the rivers and marshes and avoided the saline water further down the estuary. “I’ll explain it to Shan if that happens. She can rage at me this time.”

Ade made a vague grunt. “It’s not like the Boss to be forgiving. Maybe she’s got some problem with it.” He sounded more baffled than critical. “Maybe she can’t do it to someone she knows that well.”

“You once pulled a weapon on Lindsay Neville too, and never finished the task either.”

“If I’d known where this was going to end, don’t you think I would have?”

“No. She was your superior officer. Even if she wasn’t a marine.”

“Bullshit,” Ade said quietly, and made no sense again. “But what I cock up, I put right.”

Aras scanned the water with eyes that saw polarized light and detected the weed and movement of small creatures beneath the surface. Ade struggled with a host of unfortunate events, not just the contamination of Lindsay and Rayat—he was still grieving for the loss of a child that could never be. Aras judged this by his faint scent of anxiety at unguarded moments that could only come from unhappy thoughts.

“You have to forget the child,” said Aras.

“Can you?” said Ade.

Aras wasn’t sure, but he was trying.

“Shan had no choice. You know what a c’naatat child would mean. It would live in isolation for an unimaginable time, just as I did.”

“I know.” Ade’s blinked for a second as he sighted up through the scope of his rifle. “But can you forget it? I asked a question.”

“Wess’har have perfect recall.”

“For Chrissakes, Aras, you know what I’m asking.”

“I mourn, yes. But I know recrimination serves no purpose.”

“I’m still upset that she got rid of it.” Ade’s voice dropped, wounded and bewildered. “It would have been good to have a kid with her.”

“Think about the future for that child had it survived. Alone. Not like us. You know it was impossible.”

“Yeah. Anyway, what are we doing yakki

ng away like this when we’re doing surveillance? Maybe we should shut up.”

Aras took the hint and doubted it had much to do with stalking a target. Ade took a long, slow breath and seemed to tire of looking through the scope. He eased himself onto his knees and sat back on one heel, rifle resting in the crook of his elbow. Around them the silence was broken only by the murmur of the water and the clicks and whirrs of living things hidden in the nearby grasses.

“I did think about it,” he said at last. “And you’re right. But I really wanted a kid.”

Aras wanted a child too, perhaps more than Ade understood or Shan knew. But he was wess’har, and so what was done was done, and regret was pointless. The part of him that was human tried to indulge in what-if and if-only from time to time, but he dismissed it. It was a corrosive, destructive habit.

Instead he concentrated on an Earth he recalled but had never seen, and that same human fragment of him wanted to go back there with the Eqbas Vorhi task force. The wess’har part of him, the part that knew how the Eqbas had dealt with the isenj on Umeh, preferred not to see the invasion at all. And it would be an invasion, even if the Australians thought they were being voluntary hosts to the Eqbas fleet.

It’s going to be bloody, even with Earth’s agreement.

He decided his time was better spent healing the raw pain within his own small, bizarre family than worrying about the fate of a distant planet that had caused so much death and destruction here on Bezer’ej. And there was a lot of pain to heal.

Ade changed the subject and sighted up again. He froze, fixed on something, and his voice dropped to a whisper. “Dead ahead.”

Aras followed the direction of Ade’s focus. “What can you see?”

“Probably a sheven.” The estuary was a maze of mudflats and inlets. “It’s a bugger to spot transparent targets.”

Halo: Glasslands

Halo: Glasslands The Best of Us

The Best of Us Halo: The Thursday War

Halo: The Thursday War Ally

Ally 501st: An Imperial Commando Novel

501st: An Imperial Commando Novel True Colors

True Colors Matriarch

Matriarch City of Pearl

City of Pearl The Thursday War

The Thursday War Bloodlines

Bloodlines Gears of War: Anvil Gate

Gears of War: Anvil Gate Crossing the Line

Crossing the Line Star Wars - The Clone Wars 01

Star Wars - The Clone Wars 01 Omega Squad: Targets

Omega Squad: Targets Halo®: Mortal Dictata

Halo®: Mortal Dictata Hard Contact

Hard Contact The World Before

The World Before Order 66

Order 66 Gears of War: Jacinto's Remnant

Gears of War: Jacinto's Remnant Sacrifice

Sacrifice Triple Zero

Triple Zero Gears of War: The Slab (Gears of War 5)

Gears of War: The Slab (Gears of War 5) NEW JEDI ORDER: BOBA FETT: A PRACTICAL MAN

NEW JEDI ORDER: BOBA FETT: A PRACTICAL MAN Going Grey

Going Grey Star Wars: Boba Fett: A Practical Man

Star Wars: Boba Fett: A Practical Man Revelation

Revelation Coalition's End

Coalition's End No Prisoners

No Prisoners Star Wars Republic Commando: Hard Contact

Star Wars Republic Commando: Hard Contact Star Wars: Republic Commando: Triple Zero rc-3

Star Wars: Republic Commando: Triple Zero rc-3 The Clone Wars

The Clone Wars The Clone Wars: No Prisoners

The Clone Wars: No Prisoners Star Wars: Republic Commando: Hard Contact rc-1

Star Wars: Republic Commando: Hard Contact rc-1 Judge

Judge Omega Squad: Targets rc-4

Omega Squad: Targets rc-4 Star Wars - Republic Commando - Hard Contact

Star Wars - Republic Commando - Hard Contact